20 June – 4 August

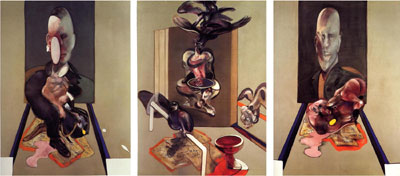

In many ways, the triptych’s form derives its potency not from historically appropriate content but, I would argue, from its unique structure. Three in one has always been a powerful formula. In this way, each individual component simultaneously sets itself apart and draws closer to its companion pieces. The result is an inevitable and attractive tension, which often pulls the viewer into the struggle. In these works by Bacon and Hirst, the formula has been shockingly realized. Brandishing the full effect of this unity within diversity, both artists impose their respective gravitational forces upon the viewer.

The multitude of Bacon’s paintings brought together for this show submerges the viewer under the weight of his emotive rage. His grotesque fascination with the mutilation of beautiful form burdens the work with countless echoes of existential doubt and longing. Maybe he has represented well the harsh emotional realities of the portrait’s subject or the artist himself, but in this way, the very choice of painting, not to mention the texture and style of the medium, merely adds to the larger prostitution of hope within his artistic vision. Ultimately, he does not capture the agony he longs to exhibit but leaves his viewer with a glimpse of the sheer horror within, a horror that cannot find a way out. Looming just beyond the edges of Bacon’s work, death waits with a patience that confounds the horror of life. If Bacon attempts to map the meaninglessness within the heart, Hirst merely pulls back the curtain shielding each life from its grim future. In this way, Hirst shares a great deal with Bacon while at the same time resolving the progression his paintings began.

The trajectory of Bacon's work has reached its terminal velocity in the clinical austerity of Hirst’s call to death. In contrast to the anatomical interest generated by Gunther von Hagens’ Body Worlds exhibitions, Hirst’s work presents through a characteristically cynical and somber lens life dissected and dismembered. Even the black monochrome triptych Forgive Me Father for I Have Sinned, 2006 captures cleverly the artist’s penchant for interrupting the viewer’s aesthetic experience with subtle reminders of the inevitable. Besides the Bosch-like texture of the triptych’s rough surface, the work preserves the unnerving smell of death beneath the layers of flies mixed in resin. In this way, this work and others incorporate a satire of the mundane into the larger scope of Hirst’s picture of death. With Like Flies Brushed off a Wall We Fall, 2006, Hirst offers his viewer the closest thing to a pretty aesthetic object that may be found in his body of work. Despite the minimalist appeal of the paintings, the viewer cannot ignore the satirical effect rendered by his choice of materials: household gloss, common butterflies and flies. Nothing signifies this mutually clinical and mundane aesthetic better than the early milestone of Hirst’s career A Thousand Years, 1990. For Hirst, death no longer looms just beyond the scope of art; it has taken centre stage.

More than a timely polemic against the pharmaceutical industry or contemporary society’s obsession with medicine, this work contains significant implications for the theologically minded. Despite the grim nature of its presentation, the sentiment is religious at its core. Humanity cannot evade it own eventuality and therefore must face it. Religion is nothing if not a means to that goal, but how hard we work to forget ourselves and our own frailty. In this way, Hirst’s greatest achievement might be the symbolic space he has created between the public’s guilty fascination with his work and their unwitting attempt to distance themselves from its latent reality.