REFLECTIONS ON RELATIONAL AESTHETICS

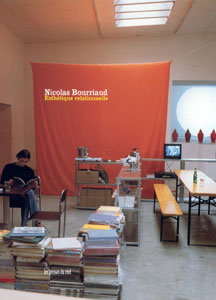

Nicolas Bourriaud.

Relational Aesthetics.trans. Simon Pleasance and Fronza Woods.

Dijon-Quetigny, France:

les presses du réel,

2002. 125pp.

I. Introduction

Commenting on the persistent desire for meaning both in art and life, Arthur Danto reflects on the future of contemporary art in a post-historical age. He writes, “What we see today is an art which seeks a more immediate contact with people than the museum makes possible… we are witnessing, as I see it, a triple transformation—in the making of art, in the institutions of art, in the audience of art.”

[1] Perceptively, Danto foresees an imminent metamorphosis necessary for the art world, but could it be fulfilled in what Nicolas Bourriaud describes as ‘relational aesthetics?’ Reflecting on a shift to ‘models of sociability’ within contemporary art of the last decade or so, Bourriaud produces a theoretical system based on the recent art attempts focused on human relationality. It remains to be seen whether or not Bourriaud’s vision fulfills Danto’s expectations, but in the interim, ‘relational aesthetics’ offers rich developments for theological dialogue with the arts.

II. Summary

By way of summary, I would like to point out the unique features of Bourriaud’s argument, with a particular focus upon the impetus for, theory and practice of ‘relational aesthetics.’ Although the ‘relational aesthetics’ movement constitutes a very recent development in contemporary art, Bourriaud has reflected effectively on a leading group of artists from the past decade or more and produced a cohesive aesthetic system to interpret these developments. Let us examine first how the movement distinguishes itself from its predecessors.

Quite conscious of the authoritative ‘post-historical’ dynamic guiding contemporary art today, Bourriaud describes carefully the way in which ‘relational aesthetics’ both rejects and incorporates the important themes modernity exercised upon art. In this way, he quips, “It is not modernity that is dead, but its idealistic and teleological version.”

[2] By this statement he means that the enthusiastic modern hopes for rational certainty or political utopias that fueled the artistic enterprise during the twentieth century have completely exhausted themselves. Thus, art no longer draws its inspiration from such optimistic visions and has turned its efforts to less grandiose projects. “Art was intended to prepare and announce a future world: today it is modeling possible universes,” microcosmic universes of authentic human sociability.

[3] ‘Relational aesthetics’ is much less a consequence of the ideological or philosophical dilemmas of modernity than merely a reaction to the practical concerns of human interaction in our present world. Consider Bourriaud’s desperate tone as he writes,

"These days, communications are plunging human contacts into monitored areas that divide the social bond up into (quite) different products. Artistic activity, for its part, strives to achieve modest connections, open up (One or two) obstructed passages, and connect levels of reality kept apart from one another. The much vaunted “communication superhighways”, with their toll plazas and picnic areas, threaten to become the only possible thoroughfare from a point to another in the human world."

[4]In his argument, technology plays a suspicious role, and Bourriaud later cautions against technological indulgence in artistic exploration. The more important theme, however, remains the endemic lose of authentic social interaction in our post-industrial age. In this way, Bourriaud holds out hope that the gallery space can surpass its role as commentator of modern life and begin providing projects of human exchange, experiments for renewed sociability. He writes, “Herein lies the most burning issue to do with art today: is it still possible to generate relationships with the world, in a practical field art-history traditionally earmarked for their “representation”?”

[5] ‘Relational aesthetics’ concerns itself with human relationality through the arts, a project rich with significance for more than just the art world. Thus, let us proceed to a discussion of Bourriaud’s theory.

As he constructs this aesthetic system, Bourriaud includes his own philosophy of art-history. Aware that art has always maintained a relational component to its self-understanding, he draws a three-tiered timeline of its development. First, in the period beginning with Classical Greco-Roman culture up to the height of Middle Ages, he sees art as an intended means of human relation to deity. Secondly, art was utilized for human relations to the physical world from the Renaissance through Modern art up to some forms of contemporary art. Finally, the third epoch of relational development began in the 1990’s with a turn toward inter-human relations and ‘models of sociability.’ Although the brevity of such a timeline may astound the reader, the gravity of his delineations cannot be ignored. Bourriaud explains his third epoch in terms of the urbanization of contemporary society. In this way, it is not hard to identify the sharp turn in contemporary art toward inter-human relations as a result or by-product of the drastic implications visited upon modern life by the increasingly urban challenges of today. As technology and urbanization relegate social functions to specific modes and spheres of experience, the spontaneity of authentic human relations is necessarily reduced. Thus, Bourriaud describes relational art as “art taking as its theoretical horizon the realm of human interactions and its social context” in contrast to a modern approach that seeks “an independent and

private symbolic space.”

[6] Employing a term used by Marx, he defines relational art as the type that “represents a social

interstice.”

[7] In other words, the work itself becomes space of potentiality, a free realm of possibility for human interaction.

In this way, Bourriaud’s theory does not centre upon ontological or teleological statements of art, but rather stresses the significance of form. “Relational aesthetics does not represent a theory of art, this would imply the statement of an origin and a destination, but a theory of form.”

[8] For him, works of art may embody or incorporate forms, which are the structures of relations and interactions between entities in the world. Bourriaud defines form as a lasting encounter, or an “independent entity of inner dependence.”

[9] Thus, unlike previous conceptions of form as ‘closed off’ by artistic style and signature, relational artists offer forms open to “the dynamic relationship enjoyed by an artistic proposition with other formations, artistic or otherwise.”

[10] Therefore, the aesthetic category of relationality organizes or determines the artistic form, so when “the aesthetic discussion evolves, the status of form evolves along with it, and through it.”

[11] As far as the task of the artist, Bourriaud envisions the artist as the mediator of specific, concrete exchanges, the perception of which results from what Félix Guattari characterizes as the awareness of subjectivity in the presence of a second subjectivity.

[12] For Bourriaud, this view of subjectivity as dependant upon the subjectivity of others supports immensely the communal aspirations of his theoretical system. This theory of ‘relational aesthetics’ necessarily places a great emphasis upon performance and participation, so let us consider his vision of the practice of relational art.

Incorporating Duchamp’s notion of “Rendez-vous d’art”- which justified works of art by virtue of their observation, Bourriaud seems to offer more implications from his theory for the art audience than the artist. As a consequence of relational art, he writes, “the artwork of the 1990’s turns the beholder into a neighbor, a direct interlocutor.”

[13] It is the subjectivity of the observer that engages the subjectivity of the artist. Thus, for ‘relational aesthetics,’ Bourriaud claims that, “meaning and sense are the outcome of an interaction between artist and beholder, and not an authoritarian fact.”

[14] The meaning that results from works of relational art comes from the interstice between artist and beholder, the attempt at momentary intimacy set apart from “the alienation reigning everywhere else.”

[15] While the artist has supplied the “conditions” for interaction in his or her work, the beholder must engage the work for it to succeed. Thus, Bourriaud offers his readers helpful criteria for such engagement:

"The first question we should ask ourselves when looking at a work of art is: - Does it give me a chance to exist in front of it, or, on the contrary, does it deny me as a subject, refusing to consider the Other in its structure? Does the space-time factor suggested or described by this work, together with the laws governing it, tally with my aspirations in real life? Does it criticize what is deemed to be criticisable? Could I live in a space-time structure corresponding to it in reality

?"

[16]In other words, Bourriaud envisions an audience response that transcends that of a “passive consumer” or mechanized witness; he sees the opportunity for a more

human encounter.

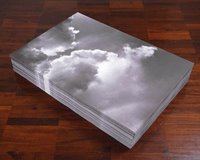

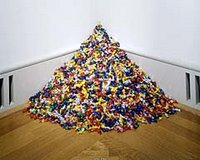

While he draws inspiration from a range of provocative contemporary artists, Bourriaud lifts up the legacy of Felix Gonzalez-Torres as exemplar of relational art. Gonzalez-Torres made a profound impact on contemporary art through his attempts at relational types of art. Consider his series of installations dedicated to his homosexual lover, Ross Laycock, who succumbed to an AIDS-related illness in 1991, five years before Gonzalez-Torres’ own death from AIDS. Variously designated

Untitled: Portrait of Ross, the memorials consist of a mound of wrapped candies or chocolates measured to Ross’ approximate body weight of 175 lbs. heaped in the corner of a gallery space. Visitors are not prohibited from taking as many candies as they wish, and the galleries are instructed to replenish the supply from time to time. Like many of his other works, the candy piles relate Gonzalez-Torres various emotions of love and loss through a participatory medium. As visitors grip their fetish-like souvenirs or enjoy a tasty treat, the encounter with the artist’s feelings about his lover’s depleting health occurs over and over again. Moreover, what surfaces is, as Bourriaud points out, Gonzalez-Torres’ enduring question: “How can a meeting between two realities alter them bilaterally?”

[17]III. Potential for Theological Engagement

In many ways, one of the most valuable aspects of contemporary art is the prevailing preoccupation with drawing attention to the often neglected or overlooked aspects of life. What the majority of self-professedly common people boycotting the galleries suggest is that art has become too unapproachable, intellectual or obtuse. Actually, for the most part, contemporary art is profoundly simplistic. In the same way that analytic philosophy has made various disciplines more precise with their use of language, the contemporary art world has demanded more precise sensibilities when it comes to their aesthetic goals. For our purposes, we must enquire what possibilities lay ahead for theological dialogue with relational art and Bourriaud’s ‘relational aesthetics.’

I would argue that theologians and churches that remain concerned about the cultural forces around them in the West would do well to learn from and appreciate the contributions of relational artists and Bourriaud’s aesthetic system. Though many may struggle in removing their aesthetic categories from Bourriaud’s first epoch of art history—due in no small part to general aesthetic ignorance amid the rising influence of institutional theories of art, all would benefit from a more participatory engagement with art. Theologians and ecclesiastical leaders that concern themselves with the influence of cultural habits or sensibilities upon the faith community must take note of the factors that have instigated the relational art movement. Faith communities should come to feel the impetus driving the movement, if they hope to minister effectively to themselves and the society around them. In short, we have much to learn from artists such as Gonzalez-Torres.

Similarly, the church has much to offer the relational art movement. Not only does the faith community dare to offer relation to the transcendent deity God through Christ the Incarnate Son, but the church also offers a restoration between human beings. Specifically, the believer’s spiritual union with Christ means a restoration of human potentiality, already experienced in this life but fulfilled in the coming kingdom. In other words, the gospel not only provides reconciliation between God and the individual, but it also provides a path of reconciliation between one individual and another, extending beyond the individual to encompass many individuals gathered together by God—‘the people of God’ as described throughout the bible. The locus of that reconciliation is the faith community gathered under the lordship of Christ and led by the Holy Spirit. Since the origins of Christianity, theologians have maintained the New Testament sense in which the faith community constitutes, along with Christ, the first fruits of the new creation. In this way, Christian theology, more than any other source, should preserve the inherent value of human relations in the post-industrial, social ghettos of modern life. In other words, we have a theological apparatus that may not only sustain dialogue with relational artists and their audiences but envision for them a tentatively present and comprehensively future restoration of human relationships through Christ. There remain great possibilities, primarily through participation, for how the theological imagination can picture for art audiences the recovery of human sociability in Christ.

IV. Conclusion

In light of the great hope that Christ holds out for a community of renewed humanity, one finds it quite disparaging to encounter artists and philosophers of art that dedicate their efforts toward authentic human interaction without certainty of its realization. Along these lines, Bourriaud concludes, “These days, utopia is being lived on a subjective, everyday basis, in the real time of concrete and intentionally fragmentary experiments. The artwork is presented as a

social interstice within which these experiments and these new “life possibilities” appear to be possible. It seems more pressing to invent possible relations with our neighbors in the present than to bet on happier tomorrows. That is all, but it is quite something.”

[18] Beyond mere experiments, can Christian community both signify and entail the hope of ‘utopian sociability?’

[1] Arthur C. Danto,

After the End of Art: Contemporary Art and the Pale of History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997) 183.

[2] Nicolas Bourriaud.

Relational Aesthetics. trans. Simon Pleasance and Fronza Woods. Dijon-Quetigny, France: les presses du réel, 2002, 13.

[3] Bourriaud, 13.

[4] Ibid., 8.

[5] Ibid., 9.

[6] Ibid., 14.

[7] Ibid., 16. Bourriaud explains Marx’s term thus, “The interstice is a space in human relations which fits more or less harmoniously and openly into the overall system, but suggests other trading possibilities that those in effect within this system.”

[8] Ibid., 19.

[9] Ibid., 19.

[10] Ibid., 21.

[11] Ibid., 21.

[12] Ibid., 91.

[13] Ibid., 43.

[14] Ibid., 80.

[15] Ibid., 82.

[16] Ibid., 57.

[17] Ibid., 52.

[18] Ibid., 45.