31.1.06

quotes...

29.1.06

art...

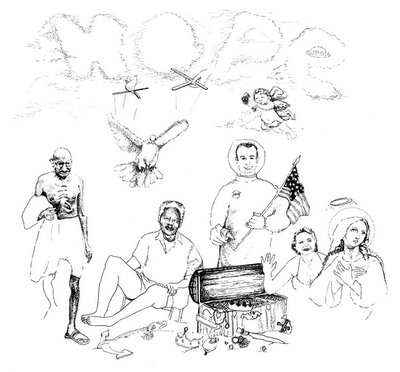

Simply titled Hope, the Linda Warren Gallery of Chicago is offering an unexpectedly candid show on that "innate human desire" during the months of January and February. Bringing together six different artists with different conceptions of hope working in different media, the show brackets out our cultural assumptions and seeks to open up a fresh dialogue on the topic. After all, in their own words--"Hope is riskier than cynicism at this moment culturally and historically." Recognizing that our polite facade of mutual hope as a society or a nation is but an "illusion of reconciliation," the show's organizer offers both artist and audience the opportunity to explore exactly how we find hope in this life.

One of the more admirable goals among contemporary artists remains their efforts in drawing attention to the oft-neglected aspects of life. In this way, Hope takes up a simple subject, yet in profound fashion. How often do we consider the ways we cope with our own existence, for meaning belies hope, and hope uncovers belief? Though we may feel the answers are beyond us, the questioning itself may be our great hope.

Please check out the details at www.lindawarrengallery.com and make the visit to Chicago for what promises to be an extraordinary experience.

24.1.06

quotes...

20.1.06

music...

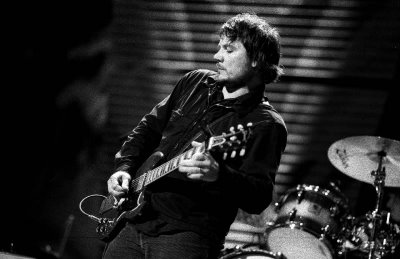

On the occasion of Wilco’s release of their much-anticipated live album, I would like to reflect on the importance of this record and the band that made it. Like so many others, my welling enthusiasm for Kicking Television: Live in Chicago shrank with bitter disappointment when I learned that their live project would be limited to a double-disc record, and not include an accompanying DVD. Instead of divulging their reasons for that choice, (for clues, however, try pondering the album’s title) I would point anyone interested to an excellent interview with Tweedy in Paste magazine.

Having just recently considered with a good friend the provocative, reoccurring phenomena of love ‘em or hate ‘em reactions to Wilco from our acquaintances, I am strangely curious about what it is that keeps me so interested in their music. For some reason, I love listening to it, playing it and thinking about it as well. It seems to really give me something to engage with; not only through the CD’s but much more so as a live concert. I guess that’s why Kicking Television has been so enjoyable for me.

For anyone that has listened carefully to the past few albums, the inevitable question remains: Can they pull off that sound live? Kicking Television obliterates that concern. The recording of those two nights in Chicago contain more sonic ambiance and spontaneity than any of the studio recordings. Not only do the guys master the precedent of their albums, but they embellish the fabric of their sound with rich, textual layers of vibrancy and colour. Encircling the core of Tweedy’s serenades and rising off the driving rhythms of Stiratt and Kotche, float the exotic jazz musings of Nels Cline on lead guitar and the soft accents of John Jorgenson’s piano. In this way, tracks like “Company in my back” and “Via Chicago” come alive in ways unimagined on the studio releases. The careful balance struck between the sombre echoes of “Jesus, etc.” and “One by one” and the raw desperation of “At least that’s what you said” and “Misunderstood” go along way in capturing the essence of their live show, evoking for me powerful memories of the emotions I experience at their show this past summer.

My fascination with Wilco, however, has not always been so strong. Just a few years ago, I heard Yankee Hotel Foxtrot for the first time and wrote it off as an Americana version of Kid A. Interestingly enough, some Reprise records exec’s must have had a similar experience; recall the now infamous tale of Wilco’s reversal of fortune with Warner Bros. immortalized by Sam Jones in the film I Am Trying to Break Your Heart. Contained within that documentary, you will find an insightful interview with a Rolling Stone editor who perceptively dissected the whole affair. Basically, he explained that the album, like others since, required a careful listen. Unfortunately, our current culture is not so keen on careful listening. But Wilco, with the help of Warner Bros., has made a prolific run at opposing that unfortunate trend in society.

While much of the so-called ‘Alt. Country’ genre is still hell-bent on the ethno-musicological interests of resurrecting an ‘old’ sound, Tweedy and the guys write songs for tomorrow through a veil of the past. With simple folk songwriting and electronicly creative arrangements in the studio space, Wilco attempts new ways of constructing, and often deconstructing, Americana. Tweedy’s unique approach gives his listeners just enough of the human touch in his lyrics to evoke resonance but keeps a certain, wary distance from autobiography. His style offers a glimpse, a window of emotion, while at the same time elusively avoiding the intense abyss of a more austerely confessional approach. Tweedy’s subtle resonances are made possible through the tempered use of soft melody and sheer noise, a soundscape representative of the all too familiar echoes of our industrial environment. Treading the aural space of a Wilco record can best be described as borrowing a friend’s daydream. Take a listen to “I am trying to break your heart” or “Radio Cure,” and see what I mean. While many may not share my appreciation for Wilco’s approach, we can all acknowledge the respect they give their audience. In an age where the music industry is frantically searching for the most cost-effective pop formulas to package scores of pre-digested tunes, Wilco requires something from its audience: imagination! To their credit, imagination is what makes Kicking Television so powerful.

More than just a great representation of their show, Kicking Television sends Wilco fans a subtle message. Unlike most other contemporary pop/rock, Wilco refuses to be just another product of their time. Their simple choice to release a live album instead of cashing in on DVD sales shows me that they expect a similar resolve from their fans. They would like to remind us that music is a gift, not merely a universal right of citizenship in this post-industrial civilization. No one is oblivious to the preponderance of music outlets available to us today. Consider how Descartes famous dictum could easily be replaced with a more updated sentiment: “I am therefore ipod.” As music has come to mean less and less to us as a culture, can we find a way to enjoy it a fresh? Maybe, but only with some imagination.

See Wilco’s site to preview or purchase Kicking Television, www.wilcoworldnet. Also, check out the Paste Magazine interview with Tweedy: www.pastemagazine.com/action/article?article_id=2421.

4.1.06

film...

Speak to me in song:

Elizabethtown and the intersection of film and popular music

How pleasant and painful art can be! I guess I should rather say good, or even great art, since many thinkers consider deep emotional reactions a superior indicator of the quality of successful works of art. Recently, we found ourselves in the midst of one such experience. Expecting merely a nice 'date movie,' Anna and I happened upon Cameron Crowe's recent film- Elizabethtown this past weekend with quite surprising results. I suppose that the fact we left the cinema in tears dictates further reflection upon this quite uncharacteristic response. Here, I will offer both reflection and review and a discussion of what I am learning through each. I am moved to offer such because I am so curious about the role and influence of popular music in not only my own life but the larger context of contemporary culture. Since confession is good for the soul, and part of my method, let's begin there.

Concerning the painful, or the melancholic rather, we could not help the longing inside us for the people and places that await us back 'home'- that which provides the landscape for Crowe's story. Filmed almost exclusively in the areas in and around Louisville, Kentucky with important references to Tennessee, Elizabethtown adopts the cultural vernacular of our home in order to communicate its tale. (Now that's a sentence pregnant with assumptions and questions!) What do I mean by a term like 'cultural vernacular?' Well, I am trying to suggest the broadest sense of visual, oral, and emotional language that I can. Trying to describe Crowe's approach, I would have to say that choosing Louisville in particular and the 'Southern' culture in general provided a unique authenticity to the story, especially for someone from this region. From the production notes available on the film's website, it is clear that filming on location was a supreme priority for the filmmakers. This commitment affords them remarkable opportunities, and along these lines, Crowe showcases poignant examples from the world of our 'home,' which would not be possible otherwise. The 'Heartland'- as referred to by the production notes, actually surfaces from the backdrop to become a very real part of the story.

I will divulge one vivid example. When Orlando Bloom's character Drew first arrives in Elizabethtown the viewer is powerfully and creatively oriented to the setting. As Drew gets out of his rental car, you witness his drastic realization of entering a previously unknown world. We watch as Drew encounters physically both the wilting oppression of Kentucky's summer humidity and the deafening din of cicada choruses. It really takes you back!

And despite the uncomfortable reminders, it is home, our home. In this way, the overall topography of the film provided us a stunning reminder of the world we left behind to come to England. So, the film showed us our homesickness, when we were barely aware of it ourselves. The timeliness of this reminder could hardly be better, since I have recently been trying to reflect on what I missed most about the cultural context we left behind. In its profound complexity, this film showed me that most of all I have been longing for that cultural fabric that holds life together, the life I know back home. I will illustrate what I mean here.

Cameron Crowe's greatest asset as a filmmaker is not any special talent that makes other directors or writers or producers great. Crowe's genius lies in an ability that almost no one else in the movie business has utilized, at least with any skill equaling that of Crowe. His fundamental approach to making films begins with a more holistic respect for life. Unlike so many others, Crowe never underestimates the value and potential of music. He understands that somewhere amid the interplay of film and appropriate music lies an undeniable emotional power. In this way, he creates a series of visual images that resonate beyond the sheer beauty of the image because the visual recognition of such is intimately linked to the emotional depth of the song or music he has carefully selected to encapsulate the scene.

For too many filmmakers, the 'soundtrack' is merely an afterthought to production, but not so for Crowe. As detailed on the website, Crowe makes popular music an intimate part of the whole process. He keeps a journal of how he intends to use specific songs in films or scenes. This process also involves incorporating those essentials songs into the casting calls as well. Crowe even uses music to 'set the stage' for a specific scene while on location. Also drawing from the input of the cast member's musical tastes, Crowe never stifles the profound influence that music can bring to film. And, the end result gains much for his creative take on music. Consider Jerry Maguire; a movie that I felt would not have made such an impact without the aid of a superior soundtrack. Or Almost Famous, more than a thoroughly interesting autobiographical tale, Crowe provides an excellent anthology of rock history throughout the story of the fictitious band Stillwater. This talent is even further developed in Elizabethtown.

If you have a special place in your heart for "mix tapes," then you will love this film. As opposed to High Fidelity, which merely philosophizes on the subject, Elizabethtown chronicles with the visual narrative the power of a 'mix tape.' Beyond giving a nod to the cultural phenomenon of 'mix tapes,' however, Crowe accomplishes so much more. Allow me to reflect on three examples that involve quite captivating expressions of the nature of human relationships.

First, Crowe captures the delightful mystique of a budding romantic connection through an unlikely choice of song. As Drew and Clare form the first fruits of romance through the free-flowing banter of an extended phone conversation, Crowe juxtaposes scenes of the two talking into the night with Ryan Adams' "Come pick me up," a melancholic gem from his first solo CD Heartbreaker. While the subject matter of Adams' song- the dark remains of betrayal and estrangement between lovers, actually communicates the opposite of what is budding between the characters in Crowe's story, the song works there. The emotional freedom and exuberance that exists between Drew and Clare in that moment of the film is actually strengthened by the wistful refrain of Adams' song. As the singer proclaims, "Come pick me up, take me out..." and expresses his regret over the loss of something special, we experience the convergence of bitter reminiscence and pining aspirations. In this way, the moment on screen deepens through the thematic intersection of memory and hope. Even if the contrast is not identified by the viewer of the subject matter portrayed by the song and the scene, the song works simply for its raw emotion. The youthful yet grave tone of Ryan Adams imparts a layer of longing that cannot be gleaned from the visual images alone. In this way, Crowe communicates a deeper level of romantic potentiality through his methodic use of popular music. Also, we can see that his approach works well with various other emotions.

Secondly, and more comically, Crowe succeeds in uniting a once disparate family group through the mutual celebration of some classic 'Southern Rock.' At a point in the film when the emotional gravity of the situation has fully emerged among several key characters, especially the chief protagonist, the family receives the opportunity to merely enjoy the moment they have together as they witness the momentous reunion of Ruckus, Cousin Jesse's failed rock group. The communal catharsis and subsequent restoration present in the cinematic moment is furthered exemplified by the song choice, what else but Lynyrd Skynyrd's "Freebird." Too long have these 'Southern Rock' ballads served as cultural anthems throughout the Southeast we may agree. We cannot, however, deny their influence, an influence quite apparent in Crowe's film. While the cultural significance of what the band represents remains an important point, the song itself speaks to the need to face one's own mortality and help others deal with the subsequent pain of loss. Recall the haunting question of Ronnie Van Zandt: "...will you still remember me?" Thus, despite the overindulgence of 'Southern Rock' clichés, "Freebird" is an appropriate embodiment of the moment. While the family struggles with the despair of death, they can also relish their togetherness and respond to the emotive invitation of the song's extended jam. It seems that Crowe may be hinting at the fact that just as Lyrynd Skynyrd goes on with life after intense tragedy so also will this family. Again, if these connections do not emerge for the film's audience, it is clear that the ecstasy that results from rockin' out on "Freebird" communicates the sort of unitive joy that Mitch desired for his families, both nuclear and extended. The humanity portrayed in this scene also proves to further authenticate the whole story. Though quite enjoyable and cathartic for the audience as well, this scene cannot compare to an even greater accomplishment of Crowe's wedding of story and song.

Third, Crowe narrates the development of the key relationship between Drew and his father through his use of Elton John's "My Father's Gun." Here, Crowe's creative technique achieves full blossom. The song reflects the experience of a young Rebel soldier's task in burying his father and taking up the inheritance of his father's legacy, symbolized by his gun. Crowe admits the singular importance of this song for the film. He relates how the transformation of the song's character provides the same emotional journey for Drew in Elizabethtown. Placed strategically near Drew's receiving the news about his own father, the song begins with the starkness of death's reality, encapsulating the sort of empty confusion and somber realizations that are no doubt plaguing Drew at the time. Unlike the Rebel son who could boldly stand in his father's place, Drew did not know his father well at all. He found himself at a loss in grieving for his father. In this way, the tension surrounding Drew's inability to mourn over his father's death builds throughout the film. When the moment finally comes, Crowe returns to "My Father's Gun," which transitions to a jubilant refrain to end the song. Once Drew deals with the reality of what has happened in his life, he has finally grasped the restoration and renewal symbolized so well in the song. Thus, Crowe has succeeded not only in giving form and shape to Drew's delayed experience of mourning but also granted the viewer a greater depth to the emotion of the story. While this is the aim of every film score, Crowe proves a master in his use of dual texts, the visual and the oral. May I add that this approach to film offers me great delight in the midst of the most bittersweet of emotional connections touched upon. Here, we have both the pleasure and the pain; now for some concluding thoughts.

There remain multiple questions surrounding this whole creative enterprise. What are the rules, if any? How do the artists' intentions compare or contrast with the resultant emotional effects that Crowe utilizes? Or better yet, what is left in his ipod when the whole process is done? Well, let's not cloud the discussion with any frivolous speculations. Crowe's mastery of the interplay between film and popular music provokes much deeper reflection than mere technique. I think that he is really on to something.

As a voracious student of popular music, Crowe seems to have a unique advantage in this respect, but I credit his sensitivity most. Not only does Crowe have intimate knowledge about the developments, origins and sources of most popular music, his greatest asset as a student of music remains his empathetic ear. He can at once feel the resonance of a great song and simultaneously envision how to portray that moment visually. In other words, Crowe simply works on the intuition that we all have. Our culture has trained us to experience life with songs, usually pop songs. There is a cultural vocabulary known only to the heart through song, and this is the great resource Crowe utilizes. In other words, popular music provides what I termed above the 'cultural fabric' of life back home.

In my own life, I recognize the power of music to generate and embody the memories that are both endearing and loathsome. They are my horror and my joy, because they are a very real part of my experience. I know that I can't escape the power that music has to deepen my own life. In this way, I will never be able to thank my father, and mother, enough for the way popular music has shaped me. They gave me a cultural language of emotion wrapped in music, the stuff with which to make sense of my own heart. And just like Crowe, I am a kid that has never really gotten over the way music so captures us in awe and wonder, takes us away and sings for us when we can't.

So, I am thankful, more than thankful, that there is a filmmaker that communicates in a language I can understand with my whole heart. While I am so far from home, adjusting to a new culture, Elizabethtown has granted me a glimpse of what I miss most. And I didn't even know that I was so homesick.

Please see the film and visit www.elizabethtown.com/home.html for the songs, interviews, videos, and more. Thanks for indulging me.