gestures...

One of the more debilitating hang-ups that Christian audiences have with both modern and contemporary art stems from a basic misunderstanding of 'artistic gestures.' The preference for gestures in works of art, beginning with the modern era of painting and evolving significantly in contemporary times, represent some unique possibilities for what art can be. Before we explore these remarkable trajectories, let me try and explain the significance of the gesture.

It may prove interesting to pause and consider what comes to mind when we think of a 'gesture.' Maybe you recall a hand signal you received on the highway or something you saw on the street in a foreign country. Perhaps, you remember the way your mother always hugs you when she first receives you. Honestly, we all may have very different associations with the term, but we can't ignore the potential depth beneath such everyday practices.

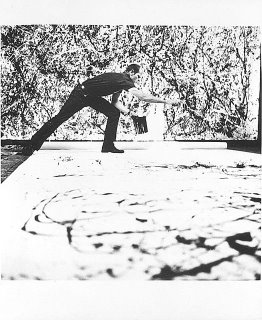

Merriam-Webster defines a gesture in this way: "a movement usually of the body or limbs that expresses or emphasizes an idea, sentiment, or attitude." It was this sort of abstract, austere definition of a gesture that we find in many famous modern paintings. We can trace the momentous transition in painting that came about possibly during or just after WWII when German or Early Expressionism (Emil Nolde, Franz Marc) gave way to Abstract Expressionism (Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Barnett Newman, Mark Rothko).

For our purposes, we can focus on Pollock, a figure from modern art much maligned but never ignored. Pollock had a powerful fascination with primal spiritualities that offered mystical connections to the 'essence of being.' In this way, he attempted to use his painting to access the primal aspects of his own being. Often referred to as "action painting," Pollock's practices generated a methodology of painting that placed the greatest emphasis on the very movements or acts that produced the work. Hence, the gesture takes the place of prominence, and the painted canvas is the mere artifact of the art action that took place. Or, in words Jerry Saltz, prominent art critic for the Village Voice in New York, used recently to describe an artist's work from this lineage: "...these paintings are narratives of their own making."

The fresh emphasis upon the artistic gesture ushered in a whole host of new questions about art. Aspects of the work that had always existed in the finished product but had not previously received the attention of the audience; such as the work's duration, location and technique. From these developments, it is not difficult to see how 'performance art' came to be (See Joseph Beuys and Yves Klein). If the gesture is valued more than what it produces, then why not gather the art audience around the gesture(s)? At that point, the audience itself took on a singular importance. Following Marcel Duchamp's notion of "Rendez-vous d'art," the work necessarily involves the observation or participation of an audience. In other words, the gesture always needs a receiver.

With performance art, we see the issue of an artifact or an end product dealt with in various ways. Sometimes the performance generates a piece of work, and sometimes the performance is only recorded through photography or other audio/visual means. In many galleries or museums, you will simply find traces or marks indicating that a work of art took place. Interestingperformanceance art seems to have diverted its future down two different roads; greater prominence for the artist as performer or a quest for increased purity of the gesture.

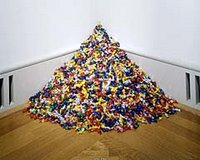

It seems that the 'relational artists' have accepted the latter for their mantle. In many cases, the audience not only experiences but receives the gesture itself or some token of it. Recall here the huge piles of candy that Felix Gonzalez-Torres left in gallery corners as a memorial to Ross. Along these lines, it should be noted that, following cultural theorists like Michel de Certeau, in our post-industrial consumer context the 'gift' proves a much stronger tool for thought than many conventional tactics. At least the form of the work requires a great deal more attention from recipient.

It seems that the 'relational artists' have accepted the latter for their mantle. In many cases, the audience not only experiences but receives the gesture itself or some token of it. Recall here the huge piles of candy that Felix Gonzalez-Torres left in gallery corners as a memorial to Ross. Along these lines, it should be noted that, following cultural theorists like Michel de Certeau, in our post-industrial consumer context the 'gift' proves a much stronger tool for thought than many conventional tactics. At least the form of the work requires a great deal more attention from recipient.

In the case of a recent exhibition at London's Institute of Contemporary Arts by Tino Seghal, I received a very odd giNaivelyvely, I happened upon last chance to catch exclusive new work, a relational art piece consisting entirely of ftravelingling conversations within the gallery. I will recount the experience briefly. Elif- a young girl of ten or eleven, met me at the door to the gallery and escorted me inside. As I observed the barren walls of the gallery, Elif asked me, "What is progress?" After spitting out a few thoughts, I wondered what was happening. Before our conversation had gotten started, Elif passed me off to Fred- a teenager of rare analytical faculties. Fred led me through the guts of the gallery; up the stairs and down the hallways. Before he had finished telling me about a Woody Allen movie I had reminded him of, Johnny entered the discussion. A man of thirty-five or so, Johnny told me several stories about people he had met and things he had read. As we walked, he learned of my studies and was commenting when... he suddenly took off down the stairs! At the bottom, Anne greeted me warmly, like the grandmother she obviously is. She reflected that progress is like a quilt that is patched together out of lots of different pieces. Anne is from the north and actually studied at Durham too. I hadn't even realized that she had led me to the gallery exit when Anne shook my hand and wished me luck. This journey took about twenty minutes.

I would describe this experience as a gift because the only artifact of the work is really the impression it made on me and what I took away. Honestly, four conversations with complete strangers these days is nothing short of an amazing gift. How many strangers do I pass everyday that aren't the least bit interested in telling me about themselves or hearing who I am?

While many would consider it very fortunate that I entered the gallery without any previous bias, I wonder what more I could have shared with these people about myself had I known what was in store. I have tried to envision what participation by Christians in relational art could be. I think it begins with a thoughtful recognition of the importance of the gesture offered and a sincere and honest response to it. Please follow the link to see an encouraging example of a recent artist's subtle, yet powerful use of gestures. See food, flowers and other stories.

2 comments:

Hey there Taylor. I enjoyed your post, and found the final encounter very interesting. My question is this...Is this example art, or is it a sociology experiment? Does the face that a gesture has been made define the event as art? Not taking away from the impact of the experience, but it seems that the performance could just as well have taken place in a lab. Has hospitality in conversation become so rare that we separate it into the realm of art? If so, it is a sad world indeed.

Thanks Ben; very interesting question and basically the biggest issue/concern of my research! (Way to hit the nail on the head!)I am considering a new post on this, but let me offer a bit of a fortaste.

In 1964, a certain philosopher of art wrote a very influential essay entitled- "the art world." Nearly forty years later and along with the help of several other philosphers of art, we have what's called the "institutional theory of art." Basically, the thinking attempts to describe and not prescribe the state of philosophy's relationship with art. They faced the question: 'how do you explain Duchamp's fountain or Warhol's brillo boxes as art?' and produced the theory of the art world. Art is defined by an art world, which includes all the developments of art history and the current participants in it (artists, critics, gallery directors, teachers, etc.). The main implication of this philosophy is that art can be whatever the art world decides or permits.

So, to answer your question, yes; the exhibit was art according to the ruling philosophy. Everyone there treated as such (the rules of that language game). While Christians experience an obvious aversion to such thinking, we must ask ourselves, forty years later, how much longer will we be disgusted at the expense of the gospel???

Post a Comment